Eating nothing but porridge for just two days could help slash ‘bad’ cholesterol and protect the heart for weeks, surprising new research suggests.

Oats have long been linked to healthier cholesterol levels – but scientists now say the effects may kick in far faster than previously thought.

Experts at the University of Bonn found that people at high risk of heart disease saw their levels of harmful LDL cholesterol, linked to higher risk of heart attack and stroke, drop by 10 per cent after following a calorie-restricted diet made up almost entirely of porridge for two days.

Oats contain beta-glucan, a type of soluble fibre known to help lower cholesterol.

It turns into a gel-like substance in the gut, which binds to cholesterol and helps stop it being absorbed into the bloodstream.

Until now, most health guidance assumed adults needed around 3g of beta-glucan daily – roughly a bowl of porridge every day – to cut cholesterol by five to 10 per cent over time.

But the new findings suggest a short, intense oat ‘reset’ could deliver a similar impact in a matter of days, particularly in people with metabolic syndrome – a cluster of conditions including obesity, high blood pressure and raised blood sugar that increases the risk of type 2 diabetes, heart disease and stroke.

The effects remained stable six weeks after the dietary intervention.

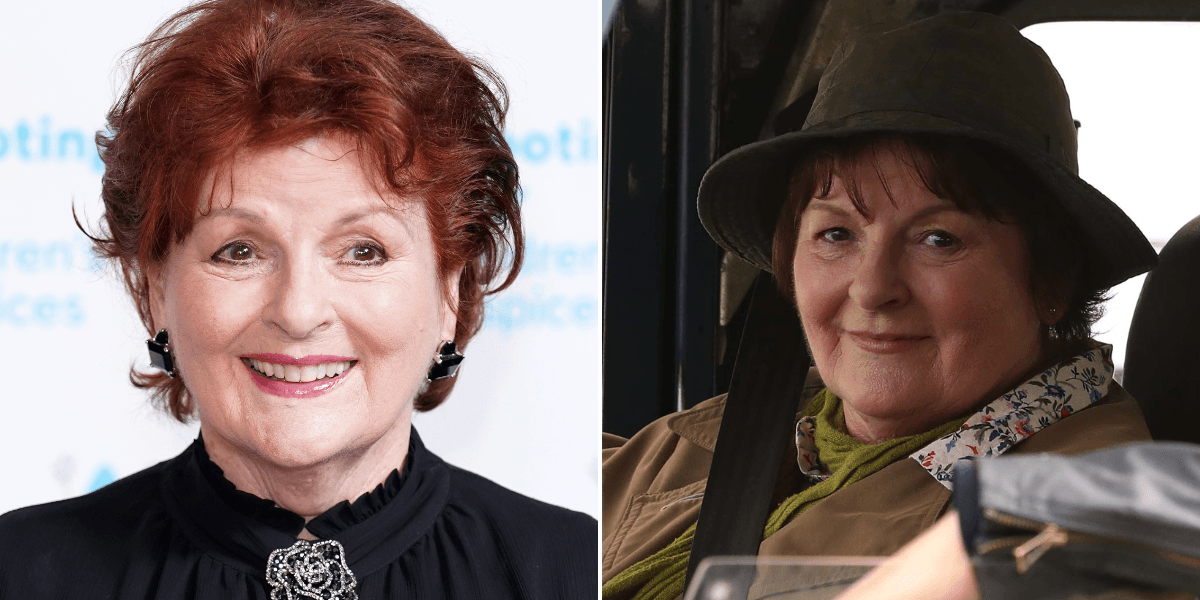

Eating porridge for just two days appears to be surprisingly effective at reducing levels of so called bad cholesterol, researchers have shown

The researchers concluded: ‘A short-term oat-based diet at regular intervals could be a well-tolerated way to keep the cholesterol level within the normal range and prevent diabetes.’

In the study, published in the journal Nature, researchers set out to determine the effects of a short-term oat diet lasting just two days, and a longer dietary intervention where participants had slightly more flexibility in terms of what they could eat.

A total of 32 participants completed the short-term diet, in which they exclusively ate porridge, divided into three 100g meals.

They were allowed to add some fruit or vegetables to their porridge, but were restricted to around half of their normal calorie intake.

The control group were also put on a calorie-restricted diet but could eat whatever they fancied.

Both groups benefited from the change in diet, but the effect was much more pronounced in those who only consumed oats.

‘The level of particularly harmful LDL cholesterol fell by 10 per cent for this group – that is a substantial reduction,’ Professor Marie-Christine Simon, expert in food science and study co-author explained.

‘They also lost two kilos in weight on average and their blood pressure fell slightly,’ she added.

To ascertain the potential long-term effects of the dietary intervention, participants were followed up six weeks after, during which time they returned to their normal eating patterns without oats.

The researchers found that eating porridge also increased the number of beneficial bacteria in the gut, including ferulic acid which has been shown to reduce cholesterol levels by inhibiting an enzyme that acts like a switch for cholesterol production.

When this enzyme is turned down, the liver produces less cholesterol, reducing fat build-up and protecting the heart.

In the longer six-week arm of the study, participants in the oat group replaced one of their normal meals with porridge, made using 80g of oats.

Those in the controlled group ate their normal diet, which did not include oats.

Interestingly, this longer intervention did not produce significant cholesterol-lowering results, suggesting that a short-term oat-based diet is more effective at reducing levels of bad cholesterol.

The team concluded: ‘Oat consumption, particularly a short-term high dose oat diet, provides metabolic health benefits.

‘Our results offer great potential since oat-based interventions, especially a short-term, high-dose oat diet, are a fast and effective approach to alleviate obesity-related lipid disorders, and they open new avenues for microbiota-targeted nutritional therapies.’

Cardiovascular disease remains the world’s leading killer, responsible for around 30 per cent of deaths and long-term disability worldwide.

More than half of UK adults are now believed to be living with high cholesterol, which can increase the risk of coronary heart disease, heart attack, and stroke.

For this reason, the NHS offers more than eight million adults statin tablets, which can bring cholesterol down to healthy levels but often have to be taken for life.

But they are not right for everyone with around half of those prescribed the tablets failing to reach healthy cholesterol levels after two years, highlighting the need for effective long-term dietary interventions.